Minneapolis

Central High School

|

Minneapolis |

|

|

Paul Norby From an E-2 to an Admiral Paul Norby started his career as a seaman second class at Wold Chamberlain field. He later flew bombers from a carrier deck in World War II. By Al Zdon There are few Navy veterans who can claim to have started as an E-2 seaman second class and ended their military career as a rear admiral. Paul Norby, who flew dive bombers from carrier decks in World War II, can make just that claim. He began his career at the bottom while learning to fly at Wold-Chamberlain Field and ended it in the lofty hierarchy of the Naval Reserve. Norby, who just turned 95, lives by himself in Minnetonka, spends time on the internet and answering his emails, and recently got together on a cruise boat on Lake Minnetonka with his World War II buddies. He grew up in several towns in Minnesota. His dad, Joseph, had graduated from St. Olaf in 1904 and had been a superintendent of schools in Madison and Fergus Falls before becoming the administrator of the Fairview Hospital in Minneapolis. Norby, who was born in 1913, graduated from Minneapolis Central in 1931, one of six kids. Since his mother too was a graduate of St. Olaf in Northfield, there was little doubt about where the children would go to college. After graduation in 1935, Norby had dreams of going on to Harvard for post-graduate work, and he even had a recommendation by the president of St. Olaf, but he was unable to secure a scholarship. This was the height of the Depression with few jobs available, and Norby turned his attention to a special program for aviation cadets. "I said, 'Why don't I try that?' There were 400 who applied, and four of us made it." Norby reported to the air station and was designated a Seaman Second Class, a rank that now would be called Seaman Apprentice. He lived at the station and took classes and learned to fly a small plane. "I can't remember what kind of plane it was, but it was a bi-plane and a tail dragger. The field was grass, and it used to be a race track. Our solo was just up and around and back." Three of the cadets passed the training and soloed. "But they could only take so many at flight training in Pensacola. So we said good bye, and the next year they called. We had to pay our own way down to Florida, and we drove down in my Model A Ford." There were five squadrons at Pensacola, teaching the cadets the different kinds of flying. By 1938, the group was ready for the fleet. "We got our wings, but we went to the fleet as cadets. We didn't know what to do with ourselves. We couldn't eat in the officer's mess, and we couldn't eat in the enlisted mess. So they had us eat with the chiefs, but they didn't want us in there listening to their conversations." Another problem was that they had studied hard at learning to fly, but not at learning life in the Navy. "We were calling the deck a floor, and the ladders stairways, and the bulkheads walls. They said, 'Those dumb cadets, all they know how to do is fly airplanes.'" Norby was assigned in 1938 to Bomber Squadron 4 on the USS Ranger, CV-4. After a year, they finally made the new fliers ensigns, the lowest ranking naval officer. The original dive bomber he flew from the Ranger's deck was the Great Lakes BG-1, a plane made in the 1930s. Only 61 were built. He later switched to the SBD Dauntless, one of the workhorses of the Navy for the next few years. The bomber was built by Northrup, and had a crew of two, a pilot and a gunner. Norby was aboard USS Saratoga when the war started. The ship was at San Diego when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. "We knew war was coming for some time. When the attack came, they froze everybody on the base. We were ordered to load live bombs for the first time. They thought the Japanese would land in Mexico and invade to the north." The ship immediately set out for Hawaii on its way to Wake Island to deliver Marine aircraft to reinforce the base there. In the end, the rescue mission was a couple days too late as the Japanese captured the island. When the ship arrived at Pearl Harbor at night, the harbor master refused to open up the nets that protected the harbor from submarines. "Instead, we spent all night out where the Japanese submarines might have been." Along the way, new metal seats were installed in the SBDs that would provide the pilots with more protection. The pilots were happy to have them, but they weren't ready for the side effects. On their way back from a flight, Norby said the squadron looked for the ship and it wasn't where it was supposed to be. "Our procedure was to drop a smoke bomb, and then conduct a search from there so we wouldn't get even more lost. We circled around, trying to figure out what had happened to the ship." Eventually, the bombers found the carrier again. "It turned out that those metal seats had an effect on the compass, knocking it 15 degrees out of whack. We got that fixed in a hurry." On another occasion, Norby and another pilot were coming back from a mission when Norby misread the flags being signaled from the flight deck. He thought the landing officer was telling him to circle around and come back and try again. "So we went round again, and came back and the ship wasn't there." It was standard procedure for ships to maintain their course so the pilots could find them, but the captain had decided to change course to "help" the errant pilots. "We did a box, flying further and further out, and then we found them." On that particular flight, Norby was flying the executive officer's plane. When he landed, the captain called for the pilot of that plane to come up the bridge, thinking it was the XO. Instead Norby presented himself. "The captain said he didn't want to see any damn cadets, and he didn't want to see me. So they called down again for whoever was flying that plane to report to the bridge. So I walked in again. He just stared at me." The captain was getting ready to let Norby have it with both barrels, but the young pilot spoke first. "I told him that two wrongs don't make a right. I admitted that I'd missed the flag signal, but that it was his job to keep the ship on course. He just looked at me, and finally he said, 'I'll remember that. You're dismissed.'" Norby said he got some unwelcome notoriety as the pilot who told the skipper what to do, but he didn't mean to show up his commander. "He was a good skipper, but he just didn't follow the plan of the day." Norby remembers one other instance when he might have been a little insubordinate. "There was a new pilot, an Academy boy. Some of those guys were good and some of them weren't." "We were going to do some night flying, and I'd been in the ready room with the red lights trying to get my night vision. After we'd launched, the new pilot was running his plane on a rich fuel mixture, and the red stream gasses were flowing off his engine and they were very bright. I radioed him to 'lean' it out, but he didn't. Later on he told me that he had changed his mixture. "I told him he should have done it when I told him to. If I lose my night vision, I might run into him or another plane." Saratoga was torpedoed southwest of Hawaii in January 1942. "We were eating when there was a thump and all the planes shook. They sounded general quarters and we headed for our ready room for orders." Because of the damage to the ship, only seven or eight planes could be launched, and Norby was piloting one of them. At the last minute, however, the aircraft he was going to take had technical problems, and he took a spare plane. "When I got in the air I realized I didn't know what kind of bomb I had attached. I just didn't look." The little squadron knew the submarine was lurking in the area somewhere waiting for the coup de grace for the carrier. They found the sub, dropped bombs and depth charges on it, and then headed back home. "When we got back to the ship, it was dead in the water and the lights were out. When they had tried to level the ship, all the boilers had gone out. The ship was without power. Because they had no power, they couldn't answer our radio calls, they couldn't talk to us." Norby and the others circled a few times and the commander of the squadron finally decided to try and make it to Pearl Harbor for a landing. "He told us to lean up the mixture until the engines were coughing and get the rpms down as much as we could. "We made it there, but we were worried they would think we were a Japanese group. The Japanese planes can't withdraw their wheels, and so when we came over Barber's Point, we kept putting our wheels up and down to show we were Americans." The pilots landed and waited for Saratoga to make it to port, which she did a couple of days later. "The guys were already welding before the ship even stopped dead." After emergency repairs at Pearl, Saratoga went back to the United States for major repairs. In late spring, Norby received orders back to shore duty. The war had just begun, but he had been at sea for three years, and the normal rotation was two years. He was sent to Miami, where for the next year and a half he trained dive bombers. Later, he became a F-4 fighter pilot and trainer at Jacksonville for six months. In early 1944, Norby, who had advanced to Lt. Commander by this time, was sent to Wildwood Naval Air Station at Cape May, New Jersey, to be the commander of 86th Bomber Squadron. It was to be assigned to the new USS Wasp, just coming out of the shipbuilding yard in Boston. The squadron joined the Wasp at Ulithi at the start of 1945, and began bombing missions over the Japanese homeland. Norby's group took over the planes of the air group that was being rotated back home. The bomber pilots were now flying the SB2C Helldiver, called the essby-duecy by the men. The pilots had to be highly skilled at landing on the carrier, catching the metal lines, and getting their plane out of the way. "Even if it only took you 30 seconds to land and move on, if you've got 70 planes in the air, that still would mean it would take 35 minutes to land them all. Some of those fighters might be short on gas." As the squadron leader, Norby would always land first and then head up to the bridge to watch the other landings. "We had a pilot one time who kept coming in and then would just go around, then he'd come in again, and just go around. He was freezing everytime he tried to land. Finally, we got on the radio and ordered him to land. "He made it, and I went out to see him. His flight suit was just soaking wet. I told him if he wanted to quit, he could." Norby recalls one bombing run over Japan later in the war when he had come in at 18,000 feet and had begun his dive. Suddenly he heard from his tail gunner, "Skipper, I've got butterflies in my stomach." Norby had little choice but to continue his attack. Later back at the ship, Norby cornered the gunner as asked him why he would say such a thing at such a critical time. "He told me, 'I don't know, I just had to talk to somebody because I was so nervous.'" On a typical mission, Norby said the fighters would go in ahead of the bombers and clear the way. Sometimes they would even drop chafe, small pieces of metal foil that would confuse the enemy anti-aircraft efforts. The Helldivers would go in at 70 degrees and about 300 miles an hour. "You tried to level out at 3,000 feet. If you missed that by about two seconds, you're in the water." Not every landing on the carrier was a smooth one. In particular, he recalls one time when he was bringing a 1,000 lb. smoke bomb out to protect the destroyer screen when the mission was canceled and all the planes were ordered back. "We knew we weren't supposed to land with a full tank, but we weren't calling the shots. So when I landed, I ruined the shocks and the wings were bent. "They wanted me to sign a piece of paper that said it was 50 percent pilot error, but I said I wouldn't do it. I never did sign that paper." On one mission, one of the flyers in Norby's squadron got hit and actually had to land on a Japanese air base in Hiroshima. He was taken prisoner and at some point later was put on a train to be taken to Tokyo. The next day the first atomic bomb was dropped on the city. Toward the end of the war, the USS Wasp was under regular attack by Japanese kamikaze planes, one of which missed the ship by just a few feet. The carrier was hit by a bomb in March, 1945. "The bomb hit right on deck, right back by the second elevator. We came back to Pearl right away." In July, the carrier returned to the war zone around Japan. When the war was over, Norby flew over Tokyo Bay when the surrender was signed. Over 500 planes were in the air. After being in the Navy for eight years, many of them at sea, he was done with military life. "I had enough points to go home two or three times. I had been lucky all the way through. I just told them I was leaving." Norby left the ship in Pearl. "I took off my flight gear and said goodbye. I got on the first ship heading back to the East Coast. Wouldn't you know it, when we were going through the Panama Canal, I looked behind and there was the damn Wasp." In all, Norby made over 380 carrier landings, one of the highest totals by any pilot in World War II. He earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for his work during the war. After the war, Norby stayed in the Reserves. He had been a lieutenant commander at the end of the war, but as time when by, he moved up the ladder. By the time he retired, he had reached the lofty rank of rear admiral. He lived in Mabel, Minnesota, for many years after the war, the hometown of his wife, Dorothy, also a graduate of St. Olaf. They had two children. Norby still brims with energy as begins his 96th year. Republished here with permission of Al Zdon of The Minnesota American Legion and Auxiliary |

Bomber Squadron 86, "The Galloping Ghosts."

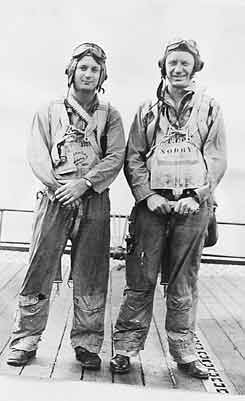

Paul Norby as a pilot in World War II.

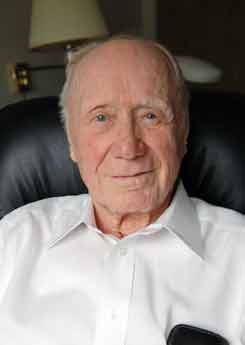

Norby at home in Minnetonka

Norby, at right, on the flight deck of the USS Wasp.

USS Wasp in an aerial photo. |